Understanding Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms and the PROVE IT Act

What Is A Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism?

Most bills to create a carbon price in the United States include provisions for a U.S. “carbon border adjustment mechanism” (CBAM) to mitigate the cost impacts of a carbon tax on U.S. manufacturers and jobs, and to promote global cooperation on carbon pricing. https://community.citizensclimate.org/content/contents/training/cbam-explainer.pdf

Also known as a border carbon adjustment, a CBAM is typically a tariff placed on goods imported from countries without an equivalent carbon price and/or carbon intensity, and a rebate on U.S. exports to those countries.

The level of the adjustment is based on the magnitude of the carbon price and the carbon content of the goods being traded.

What does a CBAM do?

Most American industries produce materials and products that tend to have a lower carbon intensity than many foreign competitors. There are a few reasons for that, even though the US hasn’t yet implemented a carbon price. For example, we have strong regulations, efficient and advanced manufacturing, and relatively clean power generation. While these factors tend to result in lower-carbon domestic products, they also add costs for American companies, which often gives dirtier foreign competition a financial advantage.

Why are carbon border adjustment mechanisms an important part of climate policy?

CBAMs would serve several goals:

- They prevent a domestic carbon fee from putting home country businesses at a disadvantage in global markets against competing producers using artificially cheap fossil fuels.

- They remove the incentive for domestic firms to relocate overseas to avoid the carbon fee, or for untaxed foreign manufacturers with higher emissions to flood the domestic market. Both forms of “leakage” would undercut the impact of a domestic carbon tax on global carbon emissions.

- Finally, they encourage foreign countries to adopt their own carbon fees so they would get the revenues instead of the country imposing the tariff, and so their manufacturers do not face a competitive disadvantage in the markets that have adopted these tariffs. This incentive will help drive global cooperation on climate solutions.

A CBAM would level that playing field by estimating the carbon intensity of certain domestic and foreign products and then imposing a carbon fee on the extra carbon content of products imported into the US. The CBAM could also refund domestic products for their lower carbon content when they’re exported across our border, so that they can better compete in other countries’ markets.

This would create a greater financial incentive to buy low-carbon products made in America, thus reducing US carbon pollution, and also encourage industries in other countries to reduce the carbon intensity of their products in order to avoid paying the CBAM. Rick described this process in easy to understand terms by using a hypothetical example of trade between the US and the fictional high-carbon country of Carbonia.

How do we create a CBAM?

Establishing a CBAM in the US would be a three step process. The first step involves calculating the carbon intensity of a variety of American industries and foreign competitors. That’s exactly what the PROVE IT Act would task the Department of Energy with doing.

Once we know the difference in carbon intensities between domestic and foreign products, the second step involves deciding the carbon price to apply to the extra carbon content of products being imported across our border. This would be simpler to do if the US had a domestic carbon price in place, which CCL will continue to advocate for. But Dana outlined a few different ways to select the CBAM carbon price, which were included in CBAM bills in the last session of Congress from Senator Sheldon Whitehouse and Senator Chris Coons.

Finally, once we know the extra carbon content of various products from different countries and the desired carbon price, the third step is to pass a CBAM bill that implements this information! Several members of Congress are reportedly working on CBAM legislation right now, so we hope to be able to dive into the details of some new CBAM bills later this year.

How much difference would a border carbon adjustment make?

In addition to covering fuels that emit greenhouse gasses when burned, proposed carbon border adjustments usually target “emissions-intensive” goods whose costs would rise substantially with a carbon price, and “trade-exposed” goods that are subject to significant competition from abroad. These products, commonly known as “Emissions-Intensive Trade-Exposed” (EITE) goods, include steel, aluminum, cement, glass, pulp and paper, chemicals, and industrial ceramics.

A landmark study by the Environmental Protection Agency in 2009 concluded that “the vast majority of U.S. industry” would be “largely unaffected” by any drag from carbon pricing on their international competitiveness. It identified only 44 out of 500 manufacturing industries, representing just 6 percent of manufacturing employment, that would be “presumptively eligible” as EITE industries for special treatment.

The models it consulted found that for the most affected sectors, a carbon price of $20 per ton of CO2 would increase production costs–and net imports–at most about 2.5 percent. Such a modest carbon price would also do little to exacerbate emissions “leakage” abroad. However, measures to level the playing field, like a border carbon adjustment, would largely eliminate both the competitive threat and any leakage.

Since then, according to the Congressional Research Service in 2022, “Some studies have questioned whether BCAs would be justified, considering the expected benefits, implementation challenges, and potential consequences that may result.” It continued:

For example, a 2017 study concluded that “our review of the economics of unilateral carbon taxes, however, does not find strong justifications for [BCAs].” A 2015 study concluded that “attempting to ‘protect’ energy-intensive U.S. manufacturing firms from international competitive pressures through various policies may have only a limited impact on these firms.… [G]iven the magnitude of the competitiveness impacts on climate policy in our simulation, the potential economic and diplomatic costs of such policies may outweigh the benefits and justify no action.”

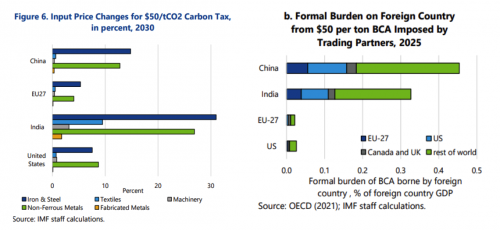

All this suggests that a BCA is not vital to the early success of carbon pricing. However, both the industry impact and rationale for BCAs will increase as countries adopt higher carbon tax levels (see figures below for a $50 tax rate). To affected workers and industries, moreover, even small percentage impacts can loom large. For that reason, BCAs may be important as a means to win political acceptance for carbon taxes even if they don’t have large-scale economic impacts.

Source: Michael Keen, et al., Border Carbon Adjustments: Rationale, Design and Impact (International Monetary Fund WP/21/239, 2021)

Would border carbon adjustments be permitted under international trade agreements?

Border carbon adjustments raise many complex issues with regard to international trade law. The United States along with most countries is a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and a signatory to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). GATT is a legal agreement to minimize barriers to international trade by eliminating or reducing quotas, tariffs, and subsidies while preserving important trade regulations. The agreement also provides a system to arbitrate commercial disputes among nations.

Most authorities agree that a properly designed border carbon adjustment would be compliant with relevant provisions of the GATT. GATT allows WTO members to impose, “on the importation of any product … a charge equivalent to an internal tax” levied on domestic producers. In 2021, WTO Deputy Director-General Jean-Marie Paugam said “nothing in the WTO rules prevents the adoption of such a mechanism by a Member if it does not constitute unjustifiable discrimination or disguised protection.” However, some proposals for a border carbon adjustment without a domestic carbon price could be judged an illegal and discriminatory tariff.

GATT’s “Most Favored Nation” principle, embodied in Article 1, requires trade without discrimination. The most favorable treatment granted one trade partner must be granted to all trade partners who signed the treaty. Signatory countries, who account for the vast majority of world trade, generally must apply the same tariff for a particular good to all trade partners. With border carbon adjustments, equal treatment means that the method of calculating adjustments for each good would not vary between trading partners. The actual fee could still vary from one trading partner to another depending on the product’s embedded carbon emissions and the partner’s carbon price.

Another important provision of the GATT states that imported goods should not be subject, directly or indirectly, to taxes or other internal charges beyond those applied, directly or indirectly, to similar domestic products. So long as the border adjustment rates are identical to the carbon fees assessed domestically, such a program would comply with this “National Treatment” provision.

Even if a trading partner considered the border adjustment discriminatory, moreover, Article 20 allows for exceptions to a practice in violation of the GATT if necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life or health, or to conserve exhaustible natural resources. Countries could also petition the WTO for a climate waiver, to clarify that there are no issues with carbon pricing and border adjustments. However, this approach is more risky.

The complexity of border carbon adjustments and climate diplomacy

Border carbon adjustments are complex to administer. Fortunately, due to the WTO requirement that each country maintain a “harmonized” tariff schedule for all imported goods, we already have a robust system in place for identifying imported or exported products that would be subject to the border carbon adjustment. Additionally, extensive work has already been done by Argonne National Laboratory and the State of California to identify the carbon content of the hundreds of different types of imported fossil fuels, so administering a border adjustment fee would be a sizable but manageable burden.

Ideally, if every major trading partner imposed a similar carbon pricing program, border carbon adjustments would not be needed. Various paths could lead to a cooperative movement toward a global carbon price. Maybe the most pragmatic and promising is a multilateral carbon price agreement among a group of nations with a border carbon adjustment that incentivizes others to join. For example, the US, Canada, Europe, China and India could start a “carbon club” with no border adjustment among them but a common border carbon adjustment for any other country without a carbon price.

Other countries are establishing CBAMs

In the meantime, several other countries are moving forward with their own CBAMs. The European Union is in the process of studying the carbon intensities of several industries, much like the PROVE IT Act would do, and will use that information to implement their own CBAM starting in 2026. Japan plans to apply a CBAM just to fossil fuels in 2028, and the United Kingdom and Canada are considering CBAMs that may look similar to the EU’s. Seeing so many allies moving forward creates extra incentive for US policymakers to implement our own CBAM here, and the PROVE IT Act would be a key first step in that process.

International actions and reactions to border carbon adjustments

The Biden administration stated in 2021, as part of its UN declaration under the Paris Agreement, “The United States will work to ensure that our firms and workers are not put at an unfair competitive disadvantage and cooperate with allies and partners that are committed to fighting climate change. As appropriate, and consistent with domestic approaches to reduce United States greenhouse gas emissions, this includes consideration of carbon border adjustments in relation to carbon-intensive goods.” In Congress, some legislators have introduced bills to put border carbon adjustments front and center, either with or without a domestic carbon price.

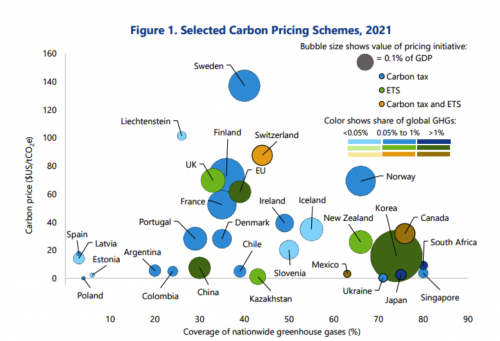

Without a domestic carbon price, however, such proposals are much harder to justify under international trade agreements and could smack of protectionism. CCL believes, both as a matter of good climate policy and to ensure compliance with international trade agreements, that a domestic carbon price should always accompany border carbon adjustments. Since nearly all major trading nations have some form of carbon pricing (see figure below), the United States will be at a competitive disadvantage if other countries begin to impose border carbon adjustments.

Source: Michael Keen, et al., Border Carbon Adjustments: Rationale, Design and Impact (International Monetary Fund WP/21/239, 2021)

In April 2023, the European Parliament approved plans for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to take effect in 2026. It would levy an import fee equal to the European Union’s carbon price on embedded carbon emissions in iron, steel, cement, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen imports from countries with no carbon price. If the United States does not implement carbon pricing by the time the CBAM takes effect, or make other political arrangements, an estimated $17 billion in U.S. exports may face added import duties. Key members of Congress have already sounded the alarm over the potential for “discrimination against U.S. businesses.” However, competitors from China and other emissions-intensive countries would face a much steeper effective tariff.

With carbon pricing now adopted in several dozen countries, interest in border carbon adjustments is spreading. The Canadian government, which administers a nationally rising carbon tax, says it is “exploring BCAs as a tool to address potential carbon leakage and any resulting competitiveness issues.” So is the United Kingdom. Japan is launching an emissions trading system that includes a border adjustment, although it only covers fossil fuels, not other carbon-intensive goods. A key policy question for the United States going forward is whether to fight back or join them in accelerating a global solution to the climate crisis.

Want to help? Make sure your members of Congress have heard from you on this issue. Send them a message with this easy, online action tool that identifies your senators for you and makes it simple to contact them supporting the PROVE IT Act. Let’s make it happen!

Previous CBAM Handouts

Looking for previous hand-outs we used to explain Border Carbon Adjustments? Here's the hand-out links:

- (0:00) Intro & Agenda

- (2:02) What is a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM)?

- (16:19) How does a CBAM work?

- (19:39) What’s happening with CBAMs in the USA and around the world?

- (22:19) What role does the PROVE IT Act play in developing a CBAM?

- (29:04) How Carbon Fee & Dividend complements a CBAM

- Dana Nuccitelli

- Rick Knight

- View or download Google Slides presentation

- Download the video

- (0:00) Intro & Agenda

- (2:02) What is a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM)?

- (16:19) How does a CBAM work?

- (19:39) What’s happening with CBAMs in the USA and around the world?

- (22:19) What role does the PROVE IT Act play in developing a CBAM?

- (29:04) How Carbon Fee & Dividend complements a CBAM

- Dana Nuccitelli

- Rick Knight

Download this episode (right click and save).

Find similar episodes on CCL's iTunes channel.

Outside Articles:

- Niskanen Center's: What Do We Know About the EU's Carbon Border Tax Proposal So Far?

- Changing Climate for Carbon Taxes – Jennifer Hillman (outside link)

- WTO-UNEP: Trade and Climate Change (outside link)

- RFF's Border Carbon Adjustments 101 and Framework Proposal for a US Upstream Greenhouse Gas Tax with WTO-Compliant Border Adjustments (outside link)

- Brookings' Adele Morris - Making border carbon adjustments work in law and practice (outside link)

CCL Blogs:

- CBAMs: What are they and why do they matter?

- How Europe's carbon pricing could affect U.S. trade

- Europe's upcoming border carbon adjustment

- Canada increasing its carbon price

- When Canada first implemented their carbon price

Laser Talks:

- Carbon Pricing Around the World (current laser talk)

- Carbon Fee Border Adjustment(current laser talk)

- Canada's Carbon Taxes (current laser talk)

- EU Border Adjustment (current laser talk)

- WTO and the Border Adjustment (old laser talk, links still good)