Canada’s Federal Carbon Pricing System

This training provides an overview of Canada's current carbon pricing system, which is a mixture of federal and provincial policies. Carbon pricing in Canada is twofold: a carbon tax on fuels and an output-based pricing system for large industrial emitters. Carbon tax proceeds are refunded to citizens and non-profits and this training highlights research from Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, The Pembina Institute, and Clean Prosperity.

Federal and provincial carbon pricing policies

Some key facts:

- The Canadian government has set minimum standards for carbon pricing that apply to all provinces

- The carbon price for fuels will rise yearly and reach $170 CAD per ton by 2030.

- Clean Prosperity modeled the impact of such a price increase prior to the government’s announcement, and that shows that it will:

- Help Canada achieve and surpass our Paris target, and;

- Get Canada two-thirds of the way towards our net-zero emissions target

- Given developments elsewhere, the Canadian government is currently considering the application of a border carbon adjustment, working in cooperation with global partners.

Carbon pricing works differently in each province and territory in Canada. Every jurisdiction must meet minimum standards as set out in federal policy and legislation.

- Federal legislation established a minimum carbon price of $20/tCO2e in 2019, rising to $50/t in 2022. These legal minimums are referred to as the federal pricing backstop.

- As long as a province/territory meets these minimum standards, it can implement and operate its own carbon pricing system. If it doesn’t meet the standards or declines to implement a system, the federal backstop kicks in.

Current status of provincial and federal carbon pricing (as of July 2021)

British Columbia and Quebec had carbon pricing prior to the 2018 federal legislation.

- British Columbia levies a carbon tax of $40/t on fossil fuels used for transportation and home heating, with revenues used to make the policy affordable for consumers and supportive of industrial competitiveness.

- Quebec operates a cap and trade system, linked with California, that covers up to 85% of industrial emissions. The auction price of carbon credits was roughly $22 CAD as of early December 2020.

Carbon pricing systems are in place in Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northwest Territories, New Brunswick, and British Columbia that meet federal benchmark stringency requirements (the backstop).

Provincial systems in place in Prince Edward Island, Alberta, and Saskatchewan also meet them for the emission sources they cover. The federal backstop supplements these systems by applying to other emissions sources the provinces do not cover.

For provinces that do not meet the federal benchmarks, the federal pricing system has two parts: a regulatory charge on fossil fuels like gasoline and natural gas, known as the fuel charge, and a performance-based system for industries, known as the Output-Based Pricing System. The fuel charge applies in Ontario, Manitoba, Yukon, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nunavut. The Output-Based Pricing System applies in Ontario, New Brunswick, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, Yukon, Nunavut, and partially in Saskatchewan.

In September 2020, New Brunswick and Ontario proposed provincial output-based pricing systems that align with the current federal benchmark. As a result, the Government of Canada is taking the necessary steps to transition from the federal Output-Based Pricing System to enable the provincial systems to take effect in New Brunswick in 2021, and Ontario in 2022.

Visit this Canadian Government web page for latest updates to provincial and federal policies.

Federal carbon tax and rebates

As one part of the two-part Canadian system, a “retail” carbon tax applies to fuels used for transportation and home heating, and is levied at the point of sale. The tax varies depending on the carbon content of the fuel.

- For 2021-22, gasoline is charged at 8.8 cents/liter, and natural gas at 7.8 cents/cubic meter.

- Ninety per cent of revenues from the tax are returned to households and 10 percent to small businesses or nonprofits, such as municipalities, schools, and hospitals in the province where they were collected.

- Rebates back to households are substantial - for example, a family of four in Ontario will get $600 in rebates in 2021; the same family in Saskatchewan will get $1,000.

- Certain fuels used in farming are exempt from the tax.

Large industrial emitters scheme

The other part of the federal policy is assessing a carbon price on large industrial emitters in the backstop provinces, known as the output-based pricing system (OBPS). Large industrial emitters account for approximately one-third of Canada’s emissions.

- OBPS applies to emitters producing more than 50 kilotons (one kiloton is 1,000 metric tons) of CO2 emissions per year (smaller facilities can opt in).

- The OBPS is not based on the amount of CO2 a facility emits, but rather how efficient it is per unit of production.

- If the facility is at least 80% as efficient (the stringency factor) as the average efficiency for producing similar products, no tax is collected. If the faculty exceeds this threshold, tax is collected per ton of CO2 emissions above the threshold.

- The system is designed to protect the competitiveness of Canadian industry and prevent carbon leakage by applying the carbon price only to emissions that exceed an emission intensity (EI) standard set for a given sector.

- The carbon price applied to industrial emissions over the sectoral EI standard is the same applied under the consumer fuel charge.

- If industrial producers pollute less than their sectoral standard, they earn credits that they can bank for the future or sell to other large emitters for compliance purposes.

- OBPS proceeds will be returned to the backstop province of origin to support industry schemes to cut emissions and use cleaner technologies. Producers will receive rebates based on the average carbon intensity of their industry.

Carbon price increases under the federal climate plan

- The federal government announced an expanded climate plan in December 2020.

- The plan proposes to increase the carbon price by $15 CAD/t per year after 2022 to reach $170 CAD/t by 2030.

- It also converted annual carbon tax rebates to quarterly payments (instead of annual tax credits) starting in June 2022.

- It proposes an increase in the stringency factor (2% per year) for industrial pricing

- The plan likewise:

- Outlines how a new national Clean Fuel Standard will cut the carbon intensity of liquid fuels and reduce GHG emissions by up to 20.6 Mt by 2030.

- Signals that the federal government will consider border carbon adjustments (BCAs), in cooperation with international partners.

Projections of emissions reductions under new price ramp

Clean Prosperity’s modeling of an increased carbon price in their November 2020 policy report shows that pricing does most of the heavy lifting to meet Canada’s Paris and net-zero targets.

Their report presented several scenarios with different carbon price increases and policies over time.

- Scenario 3 of the model most closely resembles the government climate plan in the December 2020 expansion:

- Carbon price increase of $15/t per year until 2030, then reverts to $10/t until 2040.

- The OBPS is replaced with a full price on industrial emissions - revenues go back via rebates.

- Assumes that other countries increase climate action and Border Carbon Adjustments are introduced.

- Doesn’t foresee the need for carbon pricing past 2040 given that carbon removal technologies will be operating at scale and delivering necessary emissions reductions.

- This scenario results in 159 Mt drop in emissions by 2030, and 319 Mt drop in emissions by 2040.

- This scenario gets Canada 63% of the way to the net-zero objective.

Border Carbon Adjustments (BCAs)

BCAs are being given serious consideration in the EU, US, UK, Canada and possibly among other G7 countries.

- Many trade experts believe that if designed right, BCAs could pass World Trade Organization review and be deemed free trade compliant.

- Replacing OBPS with a full carbon price applied to industry in Canada, and rebating back proceeds for goods destined for export, would:

- Reflect the true costs of industrial pollution and make carbon pricing more stringent on industry.

- Ensure fairness by making foreign consumers pay the same costs for high-carbon goods as domestic ones.

- Allow for carbon revenues to be reinvested at home in low-carbon technologies.

- Harness international trade and global supply chains to exert pressure on laggard nations to act on climate.

- Relevant federal government departments (Foreign Affairs/Trade, Environment, Finance, Natural Resources) are evaluating the prospects of applying a BCA in Canada.

Canada's Background

Note: The information below was presented in a previous (2018) training on Canada’s carbon pricing program, a part of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. The background, history, and information about studies on the impact of carbon pricing over the near term (to 2030) are still useful and relevant. Some portions of the 2018 text have been omitted due to ongoing developments.

On October 2018, in what can be described as an example of visionary leadership, the federal government of Canada announced that the Pan Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change would come into effect in 2019. Canada’s climate action plan is actually a mixture of federal and provincial initiatives with the result that carbon pricing mechanisms will be in place across the country.

Before getting into the detail of the Pan Canadian Framework, here is a profile of greenhouse gas emissions from Canada:

- In 2016 total emissions from Canada equalled 704 million metric tonnes or 1.6% of total global emissions.

- The argument is often made that whatever Canada accomplishes to curtail future emissions will have no effect on the global total.

- However, only 11 countries emit more than Canada, and the 200-or-so countries with similar and lower rates of emissions account for 35% of global emissions. If all of these countries were to ignore their regional obligations, the outcome would be catastrophic. Further, as an advanced economy, Canada has an important leadership role to play in acknowledging climate reality and taking action to implement meaningful climate action plans.

- The profile of emissions by economic sector and province reflects the contribution of the oil and gas sector to the national economy. Emissions from this sector account for 26% of the total and much of this comes from upstream release of methane from oil and gas sector activities.

- Electricity accounts for only 11% of national emissions, which is about half of what is typical for an advanced economy. The lower emissions from the electricity supply sectors stem from the extensive use of hydro across much of the country and continued use of nuclear power along with the shutdown of coal power plants in Ontario.

- Heavy industry, agriculture and waste account for the remainder of national emissions.

- Provincially, only 15% of Canadians live in the oil and gas rich provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, yet these provinces account for nearly half of national emissions. Rates of emissions on a per person basis in the remainder of the country are about fourfold less than is the case for Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth & Climate Change

Canada’s Federal Backstop Plan

- If Canada is to meet its commitment under the Paris Agreement, each province must have effective climate action plans designed to achieve meaningful targeted cuts in emissions.

- The Pan Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change provides a set of minimal standards for carbon pricing and other policies that must be met within provincial climate action plans or these will be imposed on noncompliant provinces by the federal government.

- Core to the Pan-Canadian Framework is a benchmark minimum carbon fee or equivalent applied to fossil fuels in the form of a provincial cap and trade program. Under the Pan-Canadian Framework, carbon fees start at $20 per tonne as of April of 2019 and increase by $10 annually arriving at $50/tonne by 2022.

- A system of output based allocation limits the potential for relocation of companies in emissions-intensive trade-exposed industries.

- Additional policies within the Pan-Canadian Framework include a phase-out of coal-fired power plants by 2030 and a 40-45% cut in methane emissions from the oil and gas sector to be in place by 2025.

- Finally, clean fuel standards applied to the life cycle carbon intensity of fuels is an important component of the Framework, and this measure alone is projected to reduce national emissions by about 4%.

Carbon Leakage and Output-Based Allocations

A system of output-based allocations is incorporated into the climate action plan of Alberta and is an important component of the Pan-Canadian Framework.

The system is designed to minimize the incentive for carbon leakage while retaining a market-driven pricing/trading system to incentivize industry to cut emissions. Carbon leakage refers to a relocation of emissions from a jurisdiction with effective carbon pricing in place to a jurisdiction without carbon pricing. In most cases, the process follows a physical relocation of the operations of a company.

Companies that operate within industries classified as emissions-intensive and trade-exposed could be in situations of asymmetry in carbon pricing that incentivize a relocation of operations to countries with lesser or no carbon pricing.

Output-Based Allocations start by establishing an efficiency performance standard of emissions released per unit of production.

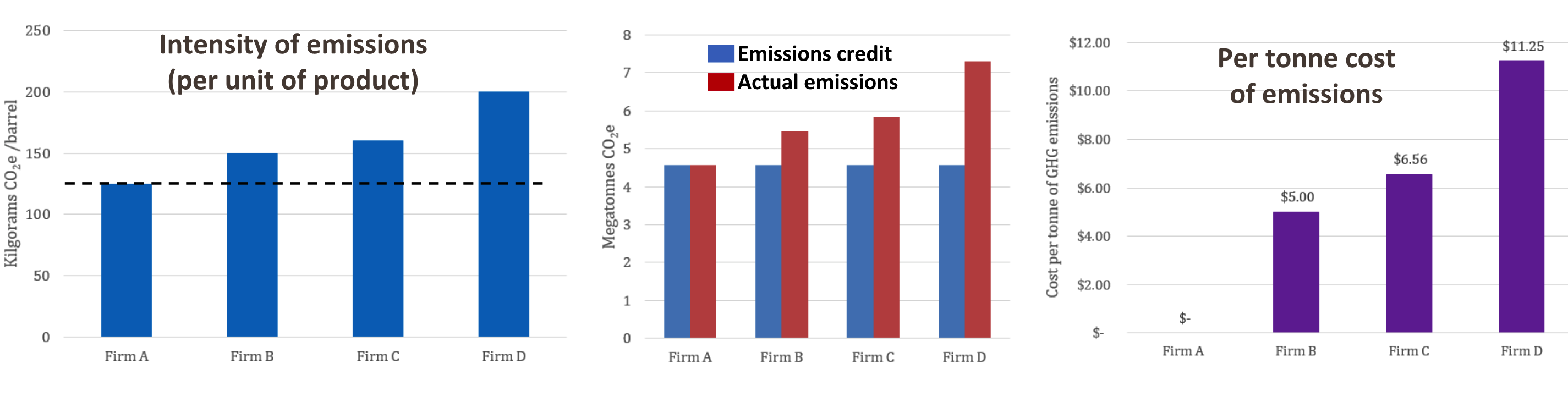

- For example, if there are four firms working in the same industry with varying rates of emission per barrel of oil produced, the emissions efficiency standard is then set to the most efficient practices of firm A.

- Each firm is then given emissions credits equal to the standard. Firm A’s actual emissions are equal to the amount of credits issued. Actual emissions exceed credits issued for firms B, C and D. Credits can be sold between companies on the open market.

- At the end of the reporting period, firms with emissions in excess of credits in hand must pay the carbon pricing fee within the jurisdiction for any emissions in excess of the credits in hand. The actual blended price per unit of total emissions will vary with the magnitude of excess emissions over credits in hand.

- Efficient companies that meet the standard do not pay carbon fees and all companies are incentivized to cut emissions.

- The system provides a break to industry while achieving a balance between maintaining the incentive to change practices and minimizing the incentive to relocate to a lower cost jurisdiction without carbon pricing.

- Output-Based Allocations must not become a haven for high emitting companies but instead must monitor transparency.

With symmetry in carbon pricing and border adjustments between jurisdictions, there is no need for Output-Based Allocations and emissions-intensive trade-exposed companies can operate without special consideration under carbon pricing mechanisms. For more information, here’s CCL Canada’s Laser Talk page on Output Based Pricing Systems.

British Columbia & Saskatchewan since 2008

A comparison of emissions and climate action policies in British Columbia and Saskatchewan illustrates the need for implementation of the federal backstop on provinces without adequate carbon pricing or a meaningful climate action plan.

- In British Columbia, absolute emissions have dropped by 5% compared to the pre-carbon tax period and sales of fossil fuel products declined by 17%. Economists estimate that carbon pricing in British Columbia’s has resulted in somewhere between a 5 to 15% cut in emissions when compared to a scenario for emissions in the absence of carbon pricing.

- In comparison, Saskatchewan had no carbon pricing or meaningful climate action plan in place since 2000. Fuel sales in Saskatchewan increased by 30% and absolute emissions went up by 7.5%.

- These differences in emissions between British Columbia and Saskatchewan cannot be attributed to differences in economic growth, as GDP growth rates were similar for both provinces.

- In Saskatchewan, 67 tonnes of GHGs are emitted per person each year. This extreme rate of per capita emissions is among the highest in the world and is over five-fold greater than the per capita emissions rates in British Columbia.

- In British Columbia, per capita emissions have fallen by over 13%, while there has been little change in per capita emissions from Saskatchewan.

This comparison provides clear evidence of the effectiveness of carbon pricing in British Columbia when compared to the lack of action on the part of the Saskatchewan government.

Pembina Institute Emissions Model For Pan-Canadian Framework

The Pembina Institute has developed a simulator that allows for comparisons of effects of various policy scenarios on future emissions from Canada extending to mid-century.

- This particular scenario assumes successful implementation of the Pan-Canadian Framework with a continuation of annual incremental increases in carbon pricing past the year 2022 (It assumes extension of carbon pricing and other policies to 2050)

- By continually increasing the price on carbon along with other policies that comprise the Pan-Canadian Framework, Canada will be able to meet the year 2030 Paris target.

- If you remove carbon pricing from the policy framework, the effectiveness of the system is grossly diminished and Canada will not be able to meet our international obligations.

- Further increases in the price of carbon will accelerate decarbonization of practices such that potentially Canada could cut emissions along a pathway that would be consistent with advanced economies driving the global effort to limit future warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius.

Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission Study on the Costs of Carbon Pricing in Canada

In 2019, Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission completed a study on the cost to the Canadian economy of implementing a national carbon price over the short-term period extending to 2027.

- This study assumes a $30 per tonne starting price that goes up by increments of $10 on an annual basis arriving at $100 per tonne by 2027.

- The revenue from the carbon fee is then recycled back to the economy by various routes, including transfer to households, transfer to industry, cuts in taxes or investment in clean technology.

- Costs are expressed as the impact on average annual growth rate of GDP.

- The take home: over the short-term with the price of carbon going up to $100 a tonne, the cost of effective climate action is negligible regardless of the mechanism of recycling carbon fee revenues.

- Projected costs are within the margin of error of the study and are consistent with the consensus coming from economists that the costs of climate action are slight over the short term period extending to 2030.

- The study goes on to conclude that, in the absence of carbon pricing, the policy framework required to achieve a 30-40% cut in emissions by 2030 is a complex and costly web of regulations that do not access the efficiencies of the marketplace.

The cost advantages of carbon pricing are enormous. The Ecofiscal Commission estimates Canada’s GDP would be 3.8% higher in 2030 with carbon pricing when compared to achieving our Paris targets using a set of regulations in the absence of carbon pricing.

Canada’s example of successful carbon pricing

The Canadian system of carbon pricing was an important subject of discussion among some high level leaders at COP26.

The Canadian government has set minimum standards for carbon pricing that apply to all provinces. Carbon pricing works differently in each province and territory in Canada. Every jurisdiction must meet minimum standards as set out in federal policy and legislation. As long as a province/territory meets these minimum standards, it can implement and operate its own carbon pricing system. If it doesn’t meet the standards or declines to implement a system, the federal backstop kicks in.

As one part of the two-part Canadian system, a “retail” carbon tax applies to fuels used for transportation and home heating, and is levied at the point of sale. The carbon price for fuels will rise yearly and reach $170 CAD per ton by 2030. The other part of the federal policy is assessing a carbon price on large industrial emitters.

Ninety per cent of revenues from the fuels tax are returned to households and ten percent to small businesses or nonprofits, such as municipalities, schools, and hospitals in the province where they were collected. About sixty percent of families come out ahead. Between 2019 and 2021, citizens received rebates via a line in income tax forms. Most people didn't know they were getting the rebates. However, in 2022, the rebates switched to four direct deposits into bank accounts.

CCL Canada was instrumental in lobbying for the Canadian carbon pricing system. In their own words:

“We did what we were told would work. We documented everything. We sent out action sheets and met every single month like clockwork. We pulled relentlessly on the five levers of political will. We submitted countless documents as citizens from across Canada to the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change.”

What does the Canadian example demonstrate?

- Political parties can get re-elected with a carbon pricing policy.

- Governments must consult all stakeholders when developing a carbon pricing policy.

- Words matter: “pricing pollution” / “making polluters pay”.

- A climate income rebate that people can see is best.

- Tax reform can pay for the low carbon transition.

- For countries with direct representation of their lawmakers build political will at the grassroots level one constituency at a time.

- Document everything.

- You have to be more than an internet group. You have to have conferences and lobbying days.

- Celebrate every success.

- Be prepared for pushback when the policy is announced.

- The policy will not be perfect on the first iteration and will need to be refined and protected for years to come.

Intro & Agenda

(from beginning)

Summary of federal and provincial carbon pricing policies

(5:21)

Federal carbon tax and rebates

(15:18)

Large industrial emitters scheme

(21:57)

Carbon price increases under new federal climate plan

(23:51)

Projections of emissions reductions under new price ramp

(28:37)

Border carbon adjustments

(31:08)

Q&A Discussion (https://vimeo.com/514675775)

- Michael Bernstein

- Cathy Orlando

Download or View Google Slides presentation.

Download the video on Vimeo.Intro & Agenda

(from beginning)

Canada's Backstop –Pan Canadian Framework

(2:10)

Output Based Allocations

(7:39)

Compliant Provincial Climate Action Plans

(11:50)

Noncompliant Provincial Climate Action Plans

(14:44)

Canadian Economic Studies

(18:14)

The Global Effort

(24:00)

Take Home Messages

(36:54)

- Michael Bernstein

- Cathy Orlando

- Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change - Government of Canada

- Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (2018)

- Laser Talk: Canada’s Carbon Taxes

- Laser Talk: Output-based Pricing Systems - CCL Canada

- Your cheat sheet to carbon pricing in Canada, June 2020 - Delphi Group

- Carbon pollution pricing systems across Canada - Government of Canada

- A healthy environment and a healthy economy, December 11, 2020 - Government of Canada (pdf)

- A Plan to Reach Net-Zero (Clean Prosperity)

- Creating Clean Prosperity: how Canada can reduce its emissions and increase its competitiveness, November 2020 (pdf)

- Canada ramps up its carbon price, moves to quarterly dividends (CCL News, by Cathy Orlando)