CCL Resources

Find print-outs, hand-outs, reports, brochures, guides, templates and a wide variety of helpful items to help you be successful.

Featured Resources

Lobby Meeting Toolkit

Step-by-step instructions, training, resources and strategies to support your fall lobby meeting

Recently updated

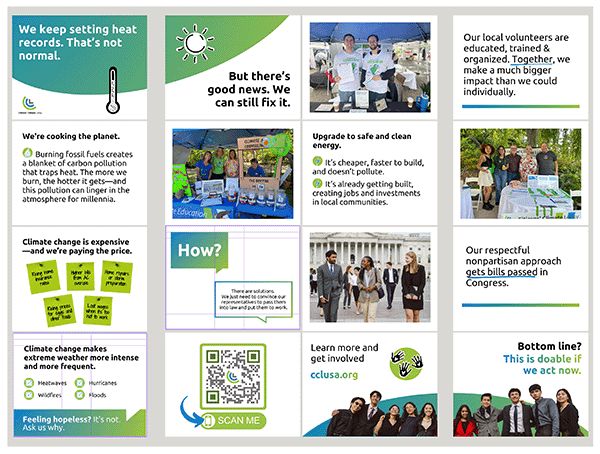

CCL Trifold Tabling Display

A printable trifold board to help you inform the public about CCL and inspire them to get involved

About CCL (Who We Are) Handouts

Use these handouts at events to educate the general public about CCL.

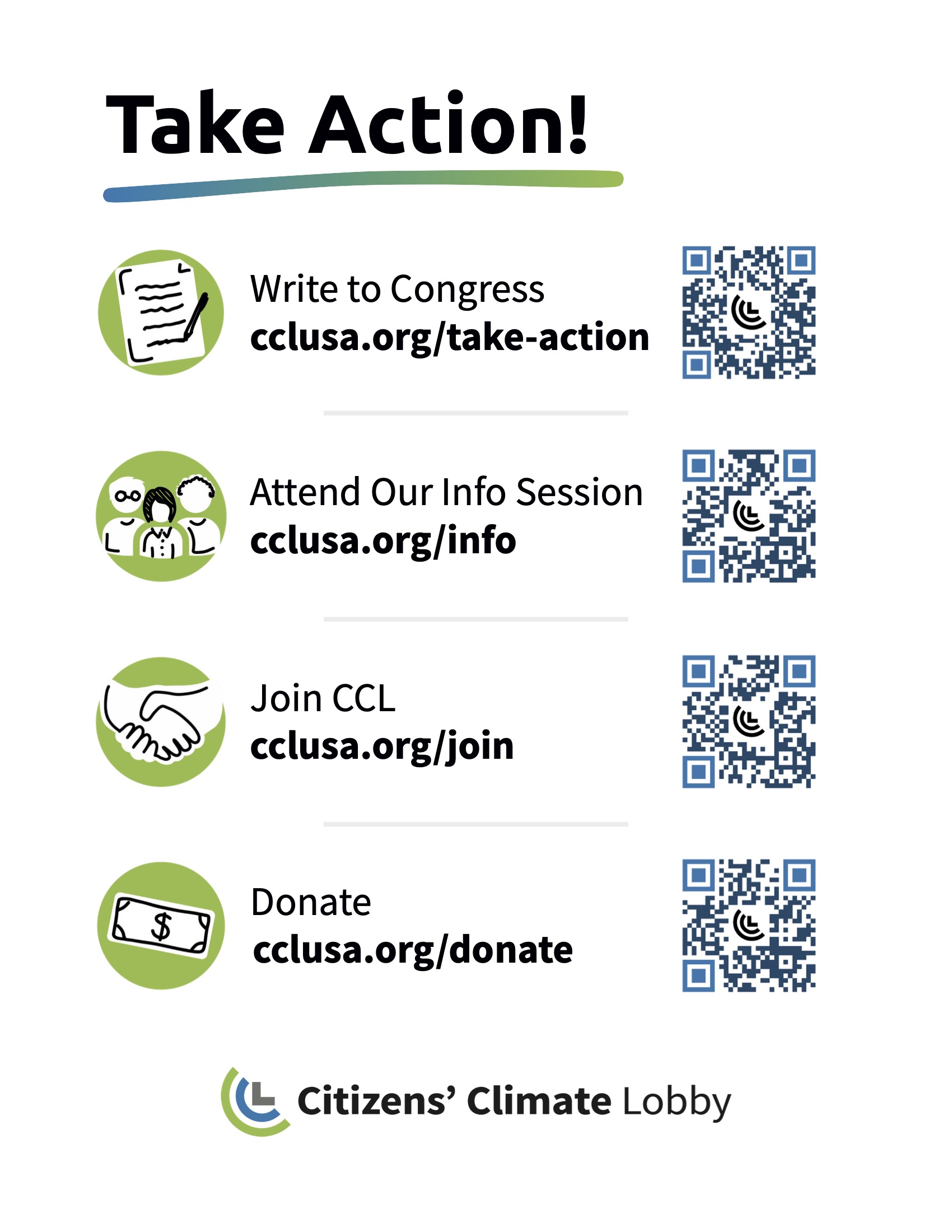

Take Action Handout

Use this handout to help direct people to CCL's online action tools.

Recently updated

Resources by category

Browse resources below by content area or type. Or scroll down to search by name, category, or format.

Table Displays and Activities

Policy and Action Handouts

CCL Recruitment Handouts, Signs and Forms